THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS – THE FINAL SHOWDOWN

Por Pedro V Roig, Esq.

Part III

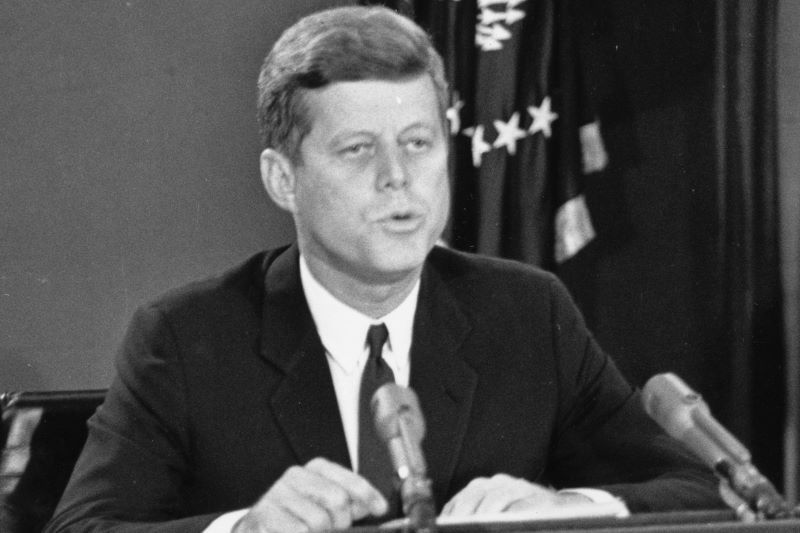

President Kennedy’s address to the nation (October 22, 1962) had the unmistakable message of an unavoidable confrontation. The Russian missiles had to be removed immediately from Cuba and returned to the Soviet Union. In addition, the President announced a strict 500 miles shipping quarantine zone around the island.

Kennedy further warned the Soviet government that the United States would “regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response against the Soviet Union.” In preparation for action the U.S. Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles were placed in full alert and the Polaris nuclear submarines in port were dispatched to preassigned stations at sea. During the president’s speech, twenty-two interceptor aircraft went airborne in the event the Cuban government reacted militarily. (Department of Defense Operations during the Cuban Missile Crisis, 2/12/63, p. 11)

In the evening of October 22, 1962, President Kennedy held a cabinet meeting and met with congressional leaders. Forty-five minutes before the President addressed the nation, NATO ambassadors received a background briefing at the State Department, while friendly military attaché were briefed at the Pentagon.

During the day, British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan was briefed by U.S, Ambassador Bruce, French President Charles de Gaulle by Dean Acheson, and West German Chancellor Conrad Adenauer by Ambassador Dowling. Mr. Acheson also briefed the NATO Council in Europe. They provided their full support to the U.S. confrontation with the Soviets.

At the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, the United States had decisive nuclear superiority over the Soviet Union. The American Nation had more than 400 Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles ICBMs compared to 78 ICBMs in the Soviet arsenals. The huge strategic advantage also included the sophisticated Polaris submarines with a devastating nuclear punch and the overwhelming striking power of some 1,300 bombers with nuclear ordinance, as opposed to less than 200 belonging to the Soviets.

THE PENKOSKY INTELLIGENCE REPORT

On October 22, 1962, Colonel Oleg Penkosky, the highest-ranking Soviet official to provide top quality missile intelligence information for the British and the U.S. including the Russian deployment of missiles in Cuba, was arrested in Moscow and later executed.

In all, Penkosky had provided the CIA and the British MI6 agencies with over 10,000 pages of intelligence reports, about 140 hours of interviews and 111 rolls of film. An artillery officer in WWII, Penkosky attended the Frunze Military Academy and in 1958 the Dzerzhinsky espionage school where he was trained as an intelligence agent and missile engineering expert.

Penkosky gave a large amount of information on the Soviet military, including photocopies of the construction plans for missile sites in Cuba, with precise technical details on their range, components and capabilities. The Penkovsky intelligence report was among the most productive clandestine operations conducted by the CIA or the British MI6 against the Soviets. The Penkovsky report gave Kennedy vital information on the Russian limited nuclear offensive capabilities. From the beginning of the confrontation the President knew the immense strategic advantage of the United States.

KHRUSHCHEV’S FALSE PRETENSE OF NUCLEAR SUPERIORITY

The Soviet Premier knew that his boisterous claim of nuclear superiority was not based on facts. During the missile crisis, Khrushchev stated that Russia was producing nuclear rockets like sausages. On this point, his son Sergei, working at a rocket design project, later told this amusing story: He said that he asked his father

“How can you say we are producing rockets like sausages… we don’t have any rockets.” To which his father answered: “That’s all right. We don’t have any sausages either.” (Thomas C. Reed, “At the Abyss.”, Ballantine Books NewYork, 2004, pp. 95).

By the time of Kennedy’s speech to the nation, Russian ships bound to Cuba were a few days away from reaching the quarantine zone. On October 23, 1962, Khrushchev received a message from the American president requesting that those ships should not cross into that zone in order to avoid a direct confrontation. Khrushchev replied: “any violations of freedom of the sea were to be considered as an act of aggression which would push mankind towards the abyss of nuclear missile war.”

It was dangerous. As Soviet ships began approaching the quarantine zone, which was 500 miles around the Cuban Island. The American Navy had specific orders not to allow the Russians ships to reach Cuba.

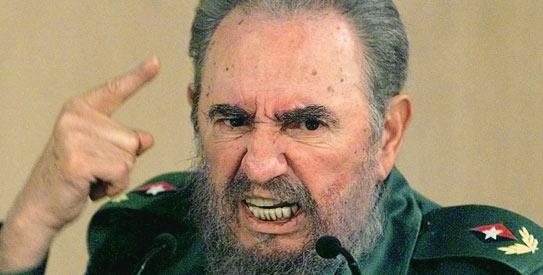

On the morning of October 23, 1962, an aggressive and enraged Fidel Castro announced a combat alarm, placing the Cuban armed forces on their highest alert. (Statement by Castro Rejecting the possibility of Inspection and Noting That Cuba Has Taken Measures to Repel a United States Attack, 10/23/62).

In the evening, the communist dictator, a compulsive liar, denies the presence of offensive missiles on Cuban soil and declares: “We will acquire the arms we feel like acquiring and we don’t have to give an account to the imperialists.” Castro also categorically refuses to allow inspection of Cuban territory, warning that potential inspectors “must come in battle array.” (Statement by Castro Rejecting the Possibility of Inspection and Noting That Cuba Has Taken Measures to Repel a United States Attack, 10/23/62)

In Washington, CIA Director John McCone Informed the President that Soviet submarines have unexpectedly been found moving into the Caribbean. According to Robert Kennedy, the president ordered the navy to give “the highest priority to tracking the submarines and to put into effect the greatest possible safety measures to protect our own aircraft carriers and other vessels.” (Document 32, McGeorge Bundy, Executive Committee Record of Action, October 24. 1062, 6:00 P.M).

The CIA also noted a statement by the president of TASS warning that U.S. ships would be sunk if any Soviet ships were attacked. (The Soviet Bloc Armed Forces and the Cuban Crisis: A Chronology July-November 1962, 6/18/63. p.50)

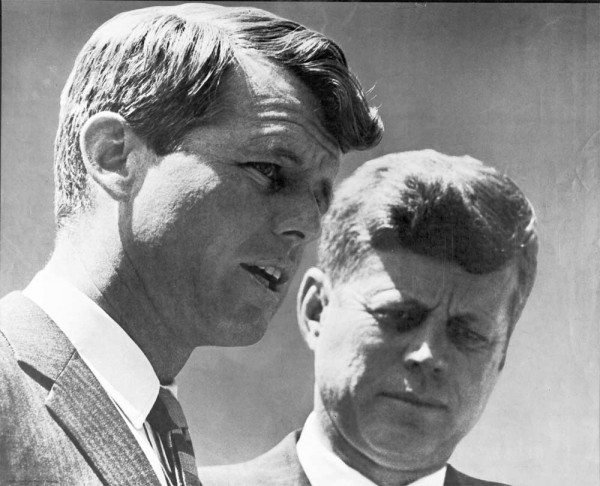

Late on Tuesday, October 23, 1962, as the Soviet ships continued to approach the quarantine zone, Robert Kennedy met with the Russian Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin. Kennedy was direct and to the point. The U.S. was ready to go into a major conflict on the issue of the deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. According to his memoirs, Dobrynin “conveyed all of Robert Kennedy’s harsh statements to Moscow.” Initially there was no reply from the Kremlin. The Soviet leadership was paralyzed and deeply confused. The Americans had called the bluff. The Soviet Ambassador described Kremlin’s leadership as being enveloped in “total bewilderment” (Dobrynin op cit p.73)

Next day, October 24, 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis reached a direct confrontation stage. The Russian ships were about to enter the quarantine zone and naval intelligence reported that a Soviet submarine had joined the ships. The aircraft carrier U.S.S. Essex, a veteran of the Bay of Pigs, was ordered to make the first interception. The showdown was fast approaching. We know today that the Soviets were not going to war over Cuba, but at the time the outlook for a nuclear conflict seemed very real.

According to dissident Soviet historian Roy Medvedev, Khrushchev responded to Kennedy by “issuing orders to the captains of Soviet ships… approaching the blockade zone to ignore it and to hold course for the Cuban ports.” Khrushchev’s order was reversed at the prompting of Politburo member Anastas Mikoyan as the Soviet ships approached the quarantine line on the morning of October 24, 1962. (Document 28, Text of President Kennedy’s Radio/TV Address to the Nation, October 22, 1962). The first sign that the Russian leadership was caving in began to appear by midmorning on Wednesday, October 24, 1962. It came to the White House in an urgent intelligence message indicating that several Russian ships near the quarantine line had stopped. At 5:15 p.m., a Defense Department spokesperson announced publicly that some of the Russian ships proceeding toward Cuba were changing their course and turning back. But still a negotiated settlement had not yet been resolved. The Russian missiles were still on Cuban 90 miles from the U.S.

On Thursday, October 25, 1962 in a briefing at the White House, the CIA indicated that some of the missiles deployed in Cuba were operational. Khushchev was attempting to gain time for full deployment of the Soviet Missiles but Kennedy immediately ordered the U.S. Armed Forces to be ready for action. Also, military targets were identified in Cuba that included three massive air strikes per day, until Castro’s air capability was destroyed.” (The Air Force Response to the Cuban Crisis, 14 October-24 November 1962. ca.1-63, 27-9.) In the morning of October 26, 1962, President Kennedy gave instructions for a provisional Cuban government to be prepared with José Miró Cardona as leader of a free Cuba, following the massive air attack and invasion of the communist Island. (CINCLANT Historical Account of Cuban Crisis, 4/29/63, P. 56; Kennedy, p. 85)

There was no room for negotiating the Soviet missile deployment in Cuba. The armed forces of the United States were ready for a fight. As a precaution, Kennedy issued the National Security action memorandum 199 authorizing the loading of nuclear weapons on aircrafts in Europe. (The Air Force Response to the Cuban Crisis 14 October-24 November 1962, ca.1/63, p. 27)

October 26, 1962 at 6:00 am, The CIA memorandum noted that construction of IRBM and MRBM bases in Cuba were proceeding without interruption. (The Crisis USSR/ Cuba: Information as of 0600, 10/26/62) At 10:00 am, President Kennedy told the ExCom that he believed the quarantine by itself would not cause the Soviet government to remove the missiles from Cuba, and that only an invasion or a trade of some sort would succeed.

The roles had been reversed. Declassified Soviet documents indicate that it was the Russian leaders who were surprised and hesitant at the firmness of the United States to wipe out the Russian missile in Cuba.

“I PROPOSE THE IMMEDIATE NUCLEAR STRIKE ON THE UNITED STATES” Fidel Castro (Oct 26,1962.)

In the evening of October 26, 1962 fearing a U.S. invasion, Fidel Castro went to the Soviet Embassy, in Havana and dictated a letter to Soviet Ambassador Alekseyev addressed to Krushchev. In his apocalyptic message Fidel Castro said: “I propose the immediate launching of a nuclear strike on the United States. The Cuban people are prepared to sacrifice themselves for the cause of destruction of imperialism and the victory of world revolution” [The New York times, Fedor Burlatsky, Oct. 23,1992]

In 1989, during a conference convened with Americans and Soviets to learn the lessons of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Sergei Khrushchev, son of the Soviet leader, who has transcribed his father’s uncensored memoirs, stated Nikita’s reaction on Fidel Castro’s message: “Is he proposing that we start a nuclear war? This is insane”. (Cuban Missile Crisis, “the Christian Science Monitor”, Anna Mulrine, October 16, 2012.) The Crisis was getting out of control. The Soviets were not ready for war. They had to get the missiles out of Castro’s insane Armageddon compulsion.

A DIRECT “CASUS BELLI” (Provoking War)

The same day that Castro sent his apocalyptic message to Krushchev (Oct 26, 1962), The Cuban communist dictator ordered his anti aircraft forces to open fire on all U.S. aircraft flying over Cuba. When the Soviet Ambassador Alekseyev requested Castro to cancel the order, it was rejected. *[Sergo Mikoyam on the Soviet views on the Missile crisis, 10/13/1987]

Then the crisis reached a breaking point when around 12 noon October 27, 1962 a U.S. reconnaissance U-2 plane was shot down over Cuba and its pilot Major Rudolf Andersson was killed. -Who gave the order to attack and destroy the U-2? The information that a Soviet general gave the order was revealed years later (1987) but in Washington it was perceived as a “Casus belli”, (Chronology of the Cuban Crisis October 15-28, 1962).

Later in the afternoon at a meeting in the White House, general Maxwell Taylor presented the U.S. Armed Forces, Joint Chief of Staff recommendation to put in effect the airstrikes and invasion of the island, but President Kennedy, immersed in his recurrent indecisiveness vacillated, stating that if an attack would happen again, he would order the destruction of the Russian missile sites and eliminate once and for all, the Castro’s totalitarian regimen.

Late that night, Robert Kennedy went to see Dobrynin. It turned out to be the decisive meeting. With the urgency of preventing a war, the Americans and the Russians worked out a formula for a negotiation of the crisis. The Soviet leadership was looking for a face-saving settlement. Under pressure of an imminent U.S. invasion of Cuba, Khrushchev told Politburo members: “Comrades, now we have to look for a dignified way out of this conflict ” (Dobrynin opcit p.85)

Robert Kennedy put forward his brother President John Kennedy’s formula that proved to be the final solution. He proposed the gradual removal of American missiles in Turkey for the immediate withdrawal of all Russian missiles and bombers in Cuba. Dobrynin immediately informed Khrushchev. In his memoirs, the Soviet Premier stated that Robert Kennedy’s offer was the turning point of the crisis [ibid 89]

Dobrynin, a highly respected diplomat, wrote: “At 4 p.m. on Sunday, October 28, I received an urgent cable from Gromyko. It read: ‘Get in touch with Robert Kennedy at once and tell him that you have couriered the content of your conversation with him to N.S. Khrushchev, who herewith gives the following urgent reply: the suggestion made by Robert Kennedy on the President’s instructions are appreciated in Moscow. The President’s message of October 27 will be answered on the radio today, and the answer will be highly positive” Robert Kennedy insisted that Turkey’s missile exchange was to remain secret for several years. He also pledged not to invade Cuba. Obviously Kennedy, supported at the time by the huge nuclear might of the U.S. failed to eliminate Fidel Castro’s regime, a brutal and aggressive Soviet ally 90 miles from continental U.S.A..

It was evident that Nikita’s bluff had failed and the nuclear missiles were removed from Cuba without consulting Fidel Castro. The Cuban Marxist dictator was publicly humiliated and his reaction against the Russian leader was violent and full of eschatological remarks. He cursed Khrushchev as a traitor and coward. The editor of Revolution, Carlos Franqui, recalled Castro screaming widely: “Son of a bitch, homosexual fagot” He was out of control. The two superpowers had relegated him to the marginal role of a disposable pawn, but in the end, he would survive in power much longer than the two world leaders. Kennedy would be assassinated a year later by Castro’s insane fanatic and Khrushchev was booted out as Prime Minister by the Soviet Politburo. But the great losers were the Cuban people, especially the younger generation forced to live in the obsolete, dysfunctional, hopeless and evil communist totalitarian dogma.