The Tactical Defensive Within the Strategic Offensive: Robert E. Lee and James Longstreet at Gettysburg

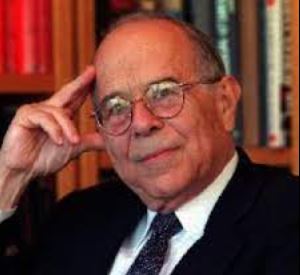

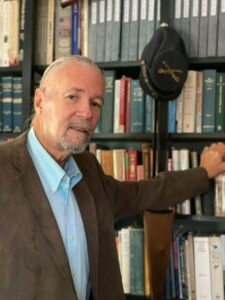

By Adolfo Ovies

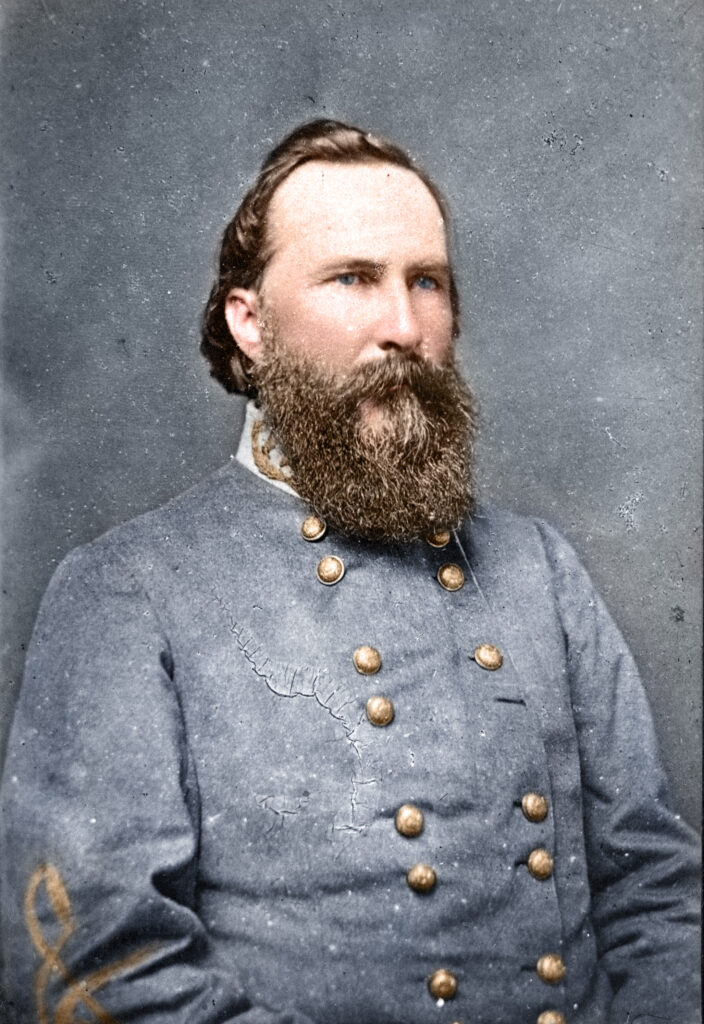

In his post-Civil War memoirs, James Longstreet would write fondly of Robert E. Lee. He characterized their relationship as “affectionate, confidential, and even tender.” Their close bond, however, would be nearly torn asunder during the battle of Gettysburg, July 1-3, 1863. The fallout of those three momentous days would have tremendous ramifications, not only on the battle itself, but on the remainder of Longstreet’s life.

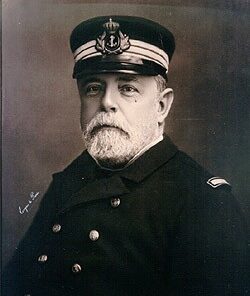

In the weeks preceding the battle, these two main commanders of the Army of Northern Virginia met to hammer out a strategic plan of action. It was Longstreet’s strongly held belief that the Confederate forces operating in Tennessee should be augmented to stymie General Ulysses S. Grant’s foreseen thrust into Kentucky. Such a move, Longstreet felt, was sure to pressure Grant into requesting reinforcements from the authorities in Washington, thus weakening their presence in Virginia. Lee favored a strategic offensive into Northern territory. His intent was to disrupt the operations of the Union forces for the duration of the summer, thus allowing Virginia’s farmers to harvest their crops to provide sustenance for his army as well as for the Southern population. In the end, Longstreet had no recourse but to obey Lee’s orders. The stage was set for the Army of Northern Virginia to make the long trek into Pennsylvania.

There was a caveat, however, in Longstreet’s acquiescence to Lee’s proposed plan. He would write, “All that I could ask was that the policy of the campaign should be one of defensive tactics that we would work so as to force the enemy to attack us . . . which might assure us of a grand triumph.” With the focus off the western front, Longstreet now wanted to interpose the Army of Northern Virginia between the Federal Army of the Potomac and Washington, thus giving rise to an inevitable battle.

Given Lee’s propensity for aggressive action, it is highly unlikely that he would have considered incorporating Longstreet’s defensive maneuvers into his plan to disrupt the Union forces. Lee referred to Longstreet’s reliance on defensive tactics as “absurd.”

Longstreet and Lee had chosen divergent views of what was to come. Lee, confident in the ability of his army and imbued with the conviction of victory, chose one path. Longstreet, his mind colored by thoughts of the carnage and bloodshed to come, struck down the other.

There is a trend in Civil War history to idolize Lee, to honor him as the greatest general of the war; but Lee made mistakes. Things started going awry for Lee almost from the start of the battle of Gettysburg. His decision to allow his Cavalry Corps commander, Jeb Stuart, to detach the bulk of his cavalry on an extended raid away from the Army of Northern Virginia, resulted in the loss of his “eyes and ears.” Then, Lee’s orders to avoid a pitched battle until he could unite all the elements of his widely scattered army failed when on July 1, Confederate General Henry Heth’s infantry ran into General John Buford’s dismounted cavalry on the outskirts of town.

Late on the first day of battle, Longstreet again approached Lee with the idea of moving around the Union flank. He was taken aback when Lee responded fiercely, “If the enemy is there tomorrow, we must attack him.” Clearly Lee’s recent successes with the forced retreat of two Federal Corps through Gettysburg and on to Cemetery Ridge, had further emboldened him. A dejected Longstreet retorted, “If he is there, it will be because he is anxious that we should attack him—a good reason, in my judgment, for not doing so.”

It was clear to Longstreet’s comrades that a palpable moroseness had settled over Lee’s “old war-horse.” Longstreet’s downward spiral continued. During the several morning hours that Lee rode to the north of the battle line on that second day of the battle, Longstreet did not initiate preparations for an offensive movement. As a result, Longstreet’s attack against the Union’s left flank was hours behind. What might have been possible early in the morning, had become more difficult as the morning wore on. Many would later claim that Longstreet had been dilatory in his movements. Others would claim that he was an obstructionist in not carrying out Lee’s orders. Longstreet harbored a deep resentment, believing that Lee had deviated from the agreed upon plan of action.

The useless loss of life incurred, by the predicted failure of Longstreet’s men to drive the Federal forces from the crest of Little Round Top, after the “best three hours fighting ever done by any troops on any battlefield” horrified Longstreet and he made one last attempt to change Lee’s mind. That night he sent scouting parties to explore the Federal’s left flank and at sunrise on the morning of July 3, he informed Lee “I have had my scouts out all night, and I find that you still have an excellent opportunity to move around to the right of Meade’s army and maneuver him into attacking us.”

The stubborn, prideful Lee went into a full rage. Bluntly he told Longstreet, “The enemy is there, and I am going to strike him.” Longstreet was adamant in his opposition to Lee’s plan to strike across the open fields and attack the entire Union army in their well-entrenched positions. Mincing no words, Longstreet told Lee, “General, I have been a soldier all my life. I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions, and armies, and should know, as well as anyone, what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men ever arranged for battle can take that position.” Lee would not be deterred.

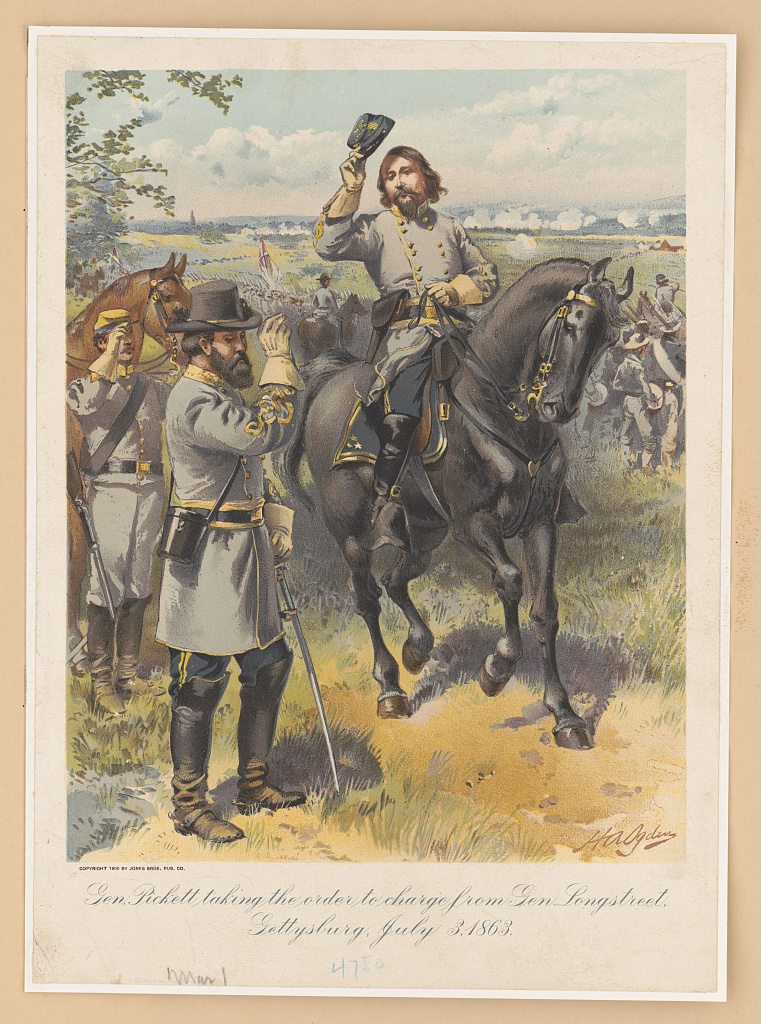

When the moment came to order General George Pickett to launch his attack, Longstreet could not look him in the eyes. The two senior generals had reached a defining moment. As the debacle that was the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble charge reached its disastrous conclusion, Longstreet would make it known that he had never been so depressed in his life. The horrendous loss of life weighed deeply on Longstreet’s soldierly beliefs. Indeed, he would spend the rest of his life dealing with the disaster. That Lee rode into the remnants of Pickett’s division and took the blame did not serve as any consolation for Longstreet. The next day, the defeated Army of Northern Virginia began its retreat to Virginia.

The battle of Gettysburg brings up several questions that historians have debated since July of 1863. Foremost among these are “Could the South have won the war?” Possibly. “Was the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg the turning point of the war?” Again, possibly. In the end, the finger of blame would point straight at Longstreet. He would spend the rest of his life attempting to set the record straight. He would fail miserably.

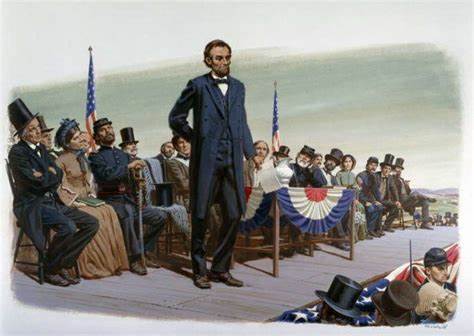

The battles around Gettysburg took place between July 1-July 3, 1863. There could be no better time to commemorate the courage and sacrifices of the men from both the North and the South who fought on those bloodstained fields than the upcoming 4th of July holiday.

NOTE: As the Cuban Center for Strategic Studies is a non-profit organization and the photos are being used for educational purposes, though some are copyrighted, their use is covered by the Fair Use Act.

Signed copies of The Boy Generals: George Custer, Wesley Merritt and the Cavalry of the Army of the Potomac, Volume 1, can be purchased by contacting Adolfo Ovies at alovies@comcast.net.