THE USS MAINE

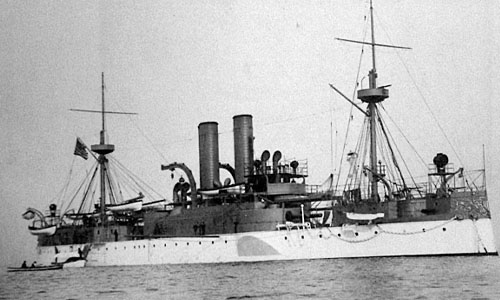

On January 24, at 11:00 in the morning, the cruisers USS Maine steam into Havana entering the narrow channel under the venerable watch of the Morro Castle and anchored in the assigned buoy number 5 close to the Spanish cruiser Alfonso XII and Ward Line Steamer City of Washington.

Secretary of the navy Richard Day and the top Spanish diplomat in Washington Dupay de Lome, arranged for a friendly visit by the Spanish cruiser Vizcaya to New York.

The first Sunday after his arrival, the Maine’s 52 -years -old captain, Charles Sigsbee, joined with a group of officers at the bullfights in Regla, where the famous matador Mazzantini (“El Torero”) performed before a roaring crowd. They were provided a ringside seat and a detachment of Spanish soldiers for protection, a wise decision given the crowd’s hostile anti-American attitude.

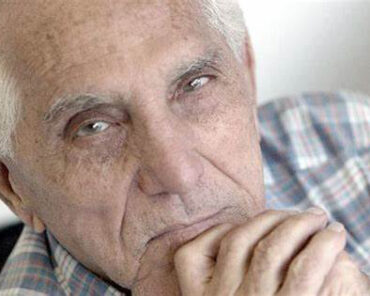

Capitan Sigsbee, an Annapolis graduate and Civil War veterans with extensive oceanographic expertise, was in charge of the 6,683-ton cruiser and its 354 officers and crew. Maine was commissioned on November 5, 1895, along with her sister ship, the Texas.

THE EXPLOSION OF THE MAINE

On February 15, 1898 at 9.40 pm, the Maine blew up and sank, killing two officers and 258 men. The warship had come to protect the lives of American citizens after the Spanish army officers ’riots three weeks early. Now it was resting at the bottom of the bay. What had happened?

In 1976, Admiral Hyman Rickover conducted an inquiry into the cause of the Maine’s demise. The result of his investigation, published in his book How the Battleship Maine Was Destroyed, points to an accident caused by coal spontaneously igniting in Bunker A-16 and the resulting fire spreading to the adjacent ammunition storage bunker, causing it to explode. It is well-established fact that the bituminous coal used by the American Navy was highly volatile and ignitable by accidental combustion. Before and after the Maine disaster, several U.S warship suffered from spontaneous fires in their coal bunkers, including the 8, 200- ton armored cruiser New York.

Sigmund Rothchild was eyewitness to the explosion. A passenger on the liner, City of Washington, anchored nearby, Rothchild was on deck facing the warship “I looked around and I saw the bow of the Maine rise a little, go a little out of the water. It couldn’t be more than a few seconds …then there came in the center of the ship a terrible mass of fire and explosion …the whole ship lifted out, I should judge about two feet. As she lifted out, the bow went right down.

A few days after the disasters, Spain and the U.S sent naval experts to determine its cause. The American team concluded that it had been an external explosion that detonated the magazine. The Spaniards arrived at the opposite conclusion, finding that external explosion was due to a tragic accident. By this time, the question of how it happened had become moot. The American press did not bother to seek a fair answer. They had already decided that Spain was guilty.

THE YELLOW PRESS DEMANDED WAR.

The Yellow Press reacted with incendiary headline. Two days after the Maine disaster, the Journal wrote “The warship Maine was split in two by an enemy secret infernal machine” America was aroused. The New York press broke the one million mark in sales, fueling the nation’s anger. The public’s animosity toward Spain became so intense, it precluded any alternative to that of military conflict. Upon hearing that the Maine had blown up in Havana’s harbor, William R. Hearst, owner of the Journal put it succinctly to his paper’s editor. “This means war.”