Spain: The Master of Europe (1520-1600)

by Pedro Roig J.D.

In November 1517, 17-year-old Charles V was crowned King of Spain. The Flanders-born regent (as an infant he spoke Dutch) was linked by blood to two of the most powerful monarchies in Europe, and so united three major European dynasties. His maternal side came from Juana [“la loca”],daughter of Isabella and Ferdinand. Charles was their grandson, and inherited a united Spain plus its American colonies, as well as Sicily, Sardinia and Naples. As the son of Philip the “Handsome” and grandson of Maximilian Hapsburg, Austria was his, as well as a preferential status toward the elective office of Holy Roman Emperor. From Mary of Burgundy, Phillip’s mother, he inherited Flanders, the Frenche-Comte and Artois. Enriched by gold from Mexico and Peru, and enhanced by the military might of the disciplined and courageous Spanish “tercios”, Charles I was the dominant monarch of Europe.

His first enterprise was to drive the French out of Italy by defeating Francis I near Milan at the battle of Pavia in 1525. But Charles lived in times of sweeping cultural change, and the challenges to his political power and religious belief became the central issues of his 40-year reign. The very autumn of Charles’ coronation, an Augustinian monk, Martin Luther, posted his 95 Propositions on the door of the All Saints Church at the University of Wittenberg, thus initiating the Protestant Reformation (1517). The Spanish Church, faced with the challenge to Roman Catholic dogma, entered a critical stage.

When attempts at conciliation failed, the Pope condemned Luther for heresy. Many German nobles endorsed the Reformation and the struggle took on a political dimension

In other parts of Europe, the Reformation continued to diversify. John Calvin preached total obedience to Scripture and stressed the concept of Predestination, the belief that every life has been predetermined by God. A sure sign of eternal salvation was earthly success, best won through hard work. Thus a strong work ethic accompanied Calvinist reform. The Calvinist accepted work as a dignity instead of a curse, wealth as a blessing instead of a crime, republican institutions as more responsive than monarchy to individual freedom. In later years, the Mayflower would take Calvinist doctrine to the English colonies in North America.

In Holland, land of the fiercely independent Dutch and one of the jewels in Charles’ crown, Calvinism gained considerable momentum in becoming an important faith. This was a disturbing challenge for the young Emperor. At first Charles tried to negotiate peacefully with the Protestant leaders, but his efforts failed. What followed was the beginning of a long and often savage religious war in which the Spanish infantry won renown as the best, most reliable force in battle. The courage and endurance of these shepherd-soldiers became legend, as well as their cruelty.

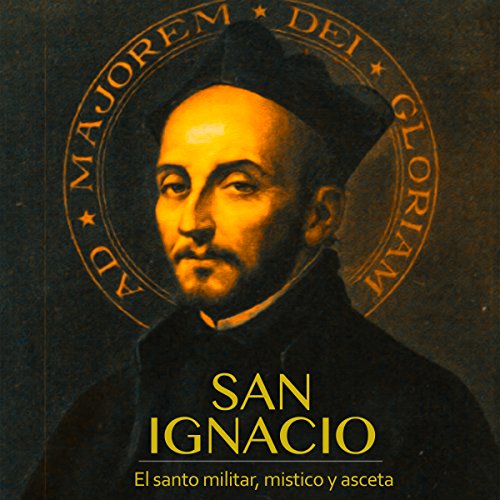

In response to the Protestant challenge, one member of the Spanish high nobility, Ignacio de Loyola, founded the Society of Jesus in 1540. The Jesuits trained and molded their members in a frugal environment that demanded obedience and discipline on physically fit bodies. They became the ideological vanguard of the counter-Reformation.

The Jesuits founded some of the most prestigious schools in Spain’s American colonies. Their outstanding teachers molded and trained many young members of the local elite in mathematics, philosophy, theology and the Greek classics. But despite the new curriculum, the Jesuits remained a dogmatic, intolerant and militant society. Their motto was direct and simple: “a la mayor Gloria de Dios” (to God’s greatest Glory).

The Jesuits can be credited with reshaping the Catholic Church message in Europe, keeping Poland, Hungary, Belgium and the southern German principalities under the spiritual leadership of the Pope. More than all the troops that fought the religious wars, the Jesuits were the Counter-Reformation’s finest soldiers, and Ignacio de Loyola one of the most influential men of his time. Cuba was negatively impacted by the gold rush of Mexico and Peru. By 1555, the island had fewer than 7,000 inhabitants.